It may not be long until we have better control over the way light from the screens on our smartphones and televisions affects our sleep quality, thanks to new technology developed by researchers at the University of Manchester and Basel.

The link between light exposure at night via screens and lower levels of sleep and sleep quality has been widely documented. Now, a research team led by Professor Rob Lucas and Dr. Annette Allen from the University of Manchester are using new technology to help combat the issue.

The team created a device called a “melanopic display.” The display allows people to adjust the level of cyan light in their screens without making noticeable changes to the screen’s true colors and overall quality.

Why is cyan light (a greenish-blue) significant? Lucas told Mattress Clarity via email that they’ve known for a while that cyan-colored wavelengths of light are especially effective at activating a type of light detector in our eye called melanopsin. “Melanopsin is thought to be very important in telling [our] body the level of ambient light,” he says.

How The Study Worked

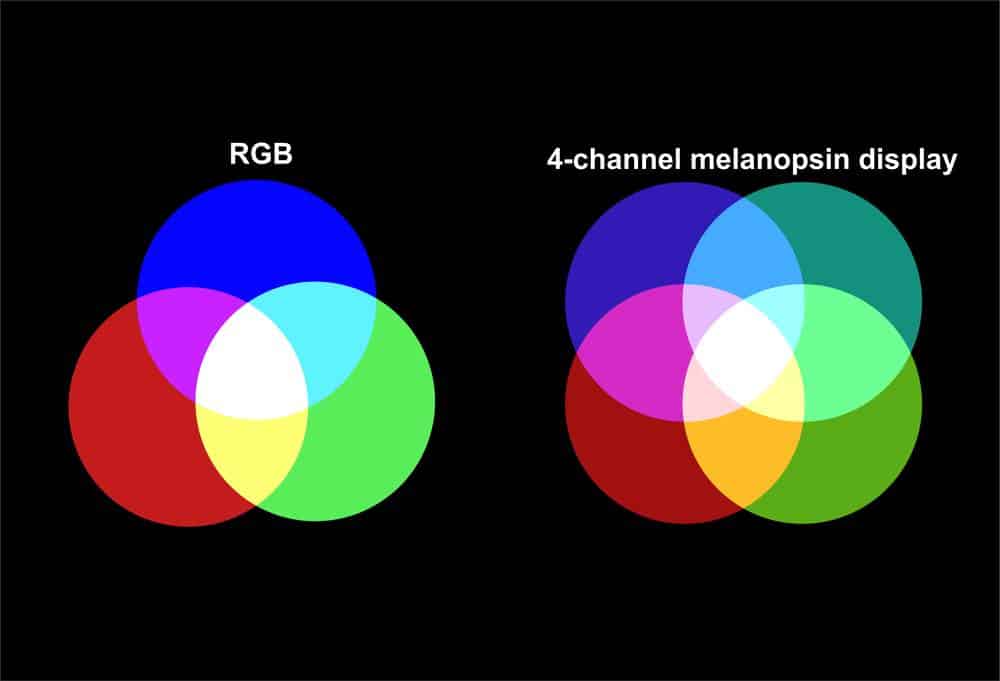

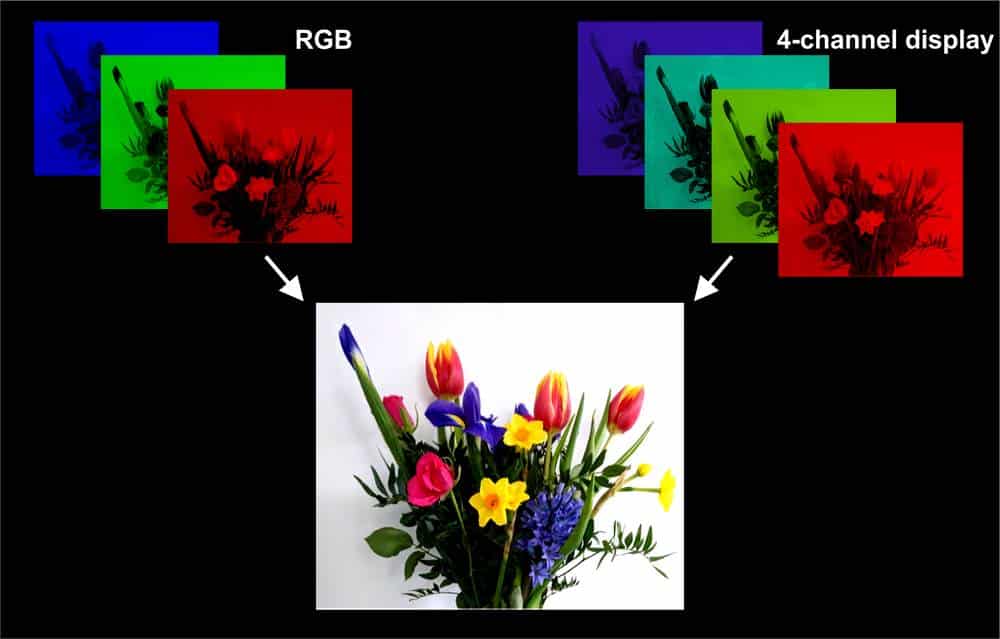

According to the researchers, conventional displays are made up of three primary colors: red, green, and blue. These colors are linked to three types of photoreceptors in our eyes. For their trial, the team added a fourth color, cyan, to the display.

The 11 participants in the trial were asked to watch a movie that either had or didn’t have cyan added as a primary color. Afterwards, they were asked to report their level of sleepiness and saliva samples were taken to detect levels of melatonin. Melatonin is a hormone our bodies produce to regulate our day and night schedules; it can usually be found in higher levels at night as our bodies prepare for sleep.

Participants reported feeling more alert when cyan levels were higher and more sleepy when the color was dimmed. Additionally, results from the trial showed higher levels of melatonin in saliva when the cyan level was lowered.

What The Results Mean

“We show that it is possible to produce colours that look the same but have different effects on our body,” Lucas told us.

He says they’re able to make these colors in a similar way to how one might mix pants. “As an example, we can produce a light that looks green by mixing yellow and blue light; you can also produce green by mixing yellow and cyan light. The two green lights look identical but our work shows that the version in which cyan light is included in the mix makes us less sleepy.” Lucas says individuals can take the same approach to other colors as well.

The ability to create colors that affect our bodies differently but that look the same means that Lucas and his team can use that property to produce a visual display that has two settings, he says.

He described these as a “staying awake setting” that uses cyan light or a “preparing for sleep setting” that omits cyan light. He say both options produce images with “perfectly natural colours.”

What Is Next?

There is a lot more to do, Lucas told us. One question his team has is whether the change in cyan light also impacts our circadian clock.

“We are also very interested in persuading visual display manufacturers to adopt our idea so that you don’t have to be a participant in one of our experiments to benefit,” Lucas said. “Instead, everyone’s smartphones. tablets, laptops and TVs could have ‘staying awake’ and ‘preparing to sleep’ settings.”

“I believe the science on this makes sense, and the corresponding product should work,” Dr. Michael Breus, a clinical psychologist and sleep expert unaffiliated with the study, told Mattress Clarity. “Obviously testing needs to be done to prove it works, but the theory seems sound.”

Breus also told us he thinks the study is more solution-based relative to previous work done on the topic. He pointed to another study from the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute that he says showed that even with the current software fixes, melatonin was still suppressed.

Breus told us that he believes the display Lucas, Allen, and their team developed could be a viable solution as an overlay.

The study was published this month in the journal Sleep and funded by the European Research Council.

Media assets courtesy of The University of Manchester

Featured image: Tero Vesalainen/Shutterstock